Table of ContentsClose

When a pregnant person has a substance use disorder, seeking treatment can be a minefield. They’re often survivors of abuse and trauma, and they may distrust a health care system that previously treated them poorly. They may also face barriers to care, especially if they live in a rural area far from a community hospital or clinic.

This means their physical and mental health needs have not been met, even before their pregnancy.

Since trauma is intergenerational, they also may have been in foster care at some point themselves, or heard stories about it, and are terrified that if they test positive for a substance—or their child does after being born—their babies will be taken away.

The answer isn’t to avoid help. It’s for health care providers to reach out to these women so they can feel safe seeking treatment. That’s the goal of the Maternal Substance Use Disorder Clinic at University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, which opened in August 2020.

Through a multidisciplinary approach that includes midwifery, OB-GYN, psychiatry, and social work, a team of practitioners works to help these patients meet their basic needs while also providing trauma-informed pregnancy care. They aim to help patients’ overall health and set them on the path toward healthy, safe, and successful motherhood.

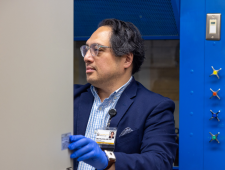

Some of these women “are scared and feel trapped. They’re worried that when they ask for help, they’ll be judged. We don’t do that here,” says Meagan Thompson, DNP, ARNP, a certified nurse-midwife at UI Hospitals & Clinics who helms the clinic. “We want these women to feel safe, secure, and treated with respect, which they may not have gotten in any other health care setting before.”

Addressing an urgent community need

Before coming to Iowa, Thompson was a midwifery student at the University of Minnesota, where she led women’s health classes with incarcerated women, most of whom had substance use disorders. When she came to Iowa, she knew she wanted to work with pregnant people struggling with the same illness.

It’s a problem that is not going away. More than 2 million people in the U.S. have opioid use disorders, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration.

That number comes from before the pandemic, which has made substance use disorders worse. More than 93,000 people in the U.S. died of overdoses of any kind in 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methamphetamine use, which Thompson says is the most common drug used by their patients, caused more than 16,500 overdose deaths in the U.S. in 2019, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Iowa is not immune to these issues. Overall, alcohol-related and drug overdoses, as of mid-2020, were on pace to increase 17% and 18%, respectively, compared to 2019, according to the 2021 Iowa Drug Control Strategy. Iowa also saw a 23% increase in opioid-related deaths between 2019 and 2020, from 157 to 212, according to the Iowa Department of Public Health (IDPH).

More than 2 million people in the U.S. have opioid use disorders.

Methamphetamine use caused more than 16,500 overdose deaths in the U.S. in 2019.

More than 93,000 people in the U.S. died of overdoses of any kind in 2020.

The Maternal Substance Use Disorder Clinic, which so far has seen more than 25 patients, works with women who use opioids, methamphetamine, heroin, and/or marijuana. Sarah Hambright, a social worker who joined the clinic in October 2020, says many of these women have trauma in their pasts. They also face a steep climb to accessing care, usually related to living in poverty.

The clinic wants to help remove some of those hurdles.

“We consider all social determinants of health when helping these women,” Hambright says.

For those living in rural Iowa, this includes transportation issues. Rural Iowa is considered a maternity care desert. When rural hospitals closed or shuttered OB-GYN services, these women had no choice but to trek far for medical care—or not receive it at all. Half of the clinic’s patients must travel roughly an hour or more each way to receive care, without having access to reliable transportation.

Many are also unhoused. For those who do have housing, it’s sometimes temporary, and they’re worried about losing their jobs and/or apartments if they partake in treatment for their illness.

“They can’t afford their rent, can’t afford to stop working, or they’re homeless,” Thompson says. “Some of our patients have been in homeless shelters. It’s a chaotic life, which can make maintaining regular health care appointments difficult.”

These mothers are also concerned about what happens after they give birth if their substance use disorder is disclosed or discovered, or if their baby tests positive for substances.

“They are absolutely terrified about involvement with the Department of Human Services (DHS), whether that’s from their own personal experience or experiences they’ve heard from other people,” Thompson says. “Our belief is that mother and baby are safest together in a safe environment. DHS is on the same page, and we want them to overcome these barriers to keep them together.”

At the same time that they are dealing with what can be overwhelming challenges related to their substance use disorder, they also have specific health needs and risks in pregnancy. Pregnant women with substance use disorders, especially related to opioids, are at higher risk for miscarriage and stillbirth, and their babies are also more likely to be born early and have a low birth weight.

The first year postpartum may also be a dangerous one: Opioid overdose deaths decline during pregnancy and peak seven to 12 months postpartum, according to a 2018 study published in the journal Obstetrics & Gynecology.

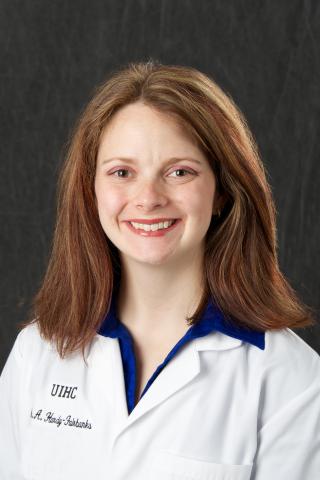

The benefit of the Maternal Substance Use Disorder Clinic, says Alison Lynch (98MD, 03R), UI clinical professor of psychiatry and family medicine, is that the health care professionals involved in patient care don’t stigmatize their patients.

“We recognize that they are dealing with a health condition that doesn’t just turn on and off, and it’s not about choices or not wanting [treatment] hard enough,” says Lynch, who is also the director of the UI Addiction Medicine Clinic. “To watch them be able to get treatment and be treated with respect ... I’ve seen so many people transform their lives when they do get access to care.”

The clinic often refers patients to in-demand UI psychiatry and addiction specialists. Lynch acknowledges that this increased demand creates challenges in providing timely care and follow-up but also illustrates the magnitude of the problem.

“If anything, this demonstrates that we need more psychiatrists and addiction medicine providers in the state,” she says.

Lynch notes that in 2020, the Department of Psychiatry received funding to establish an addiction medicine fellowship to train more physicians in the rapidly growing field.

MATERNAL SUBSTANCE USE DISORDER CLINIC

No judgement, no scorn. Instead, providers in this clinic take a trauma-informed, harm-reduction approach to care. Those working in the clinic recognize that pregnant women who have substance use disorders most likely have been abused and traumatized, which plays both a role in their addiction and their fear and mistrust of health care providers.

How the clinic works

Through an IDPH grant, the program was designed to increase screening rates for substance use for pregnant women. At OB-GYN clinics at UI Hospitals & Clinics, all pregnant women are screened at their first obstetrics visit and again at 28 weeks. If a woman discloses that she uses substances, or she tests positive on a urine drug screen, she is asked if she’d like to be referred to the clinic.

Hambright adds that they also coordinate with different agencies in Iowa “to let them know our clinic exists, so we can help the greatest number of patients that we can.” They also emphasize to these agencies that they will work with anyone from around the state, not just those who live near Iowa City.

“It’s really common, after being a victim of abuse and assault, to channel really strong negative emotions inward, such as shame, worthlessness, and lack of self-esteem, all of which are fuel for substance use,” she adds.

The approach is different than what these women might have seen in other health care settings. There is no judgment or scorn; instead, practitioners take a trauma-informed, harm-reduction approach. Those working in the clinic recognize that these women most likely have been abused and traumatized, which plays both a role in their addiction and their fear and mistrust of health care providers.

Trauma, such as physical or sexual abuse, are extremely common in this patient population, Lynch says.

Keeping those trauma experiences front and center means that being pregnant and being vulnerable is often very scary, especially when patients have a history of being abused, according to Thompson.

“That means always respecting people’s autonomy and always asking people’s permission and checking in and reading their body language to make sure they’re comfortable with whatever we’re doing," she says.

The role of social work at the clinic is to help women access transportation and obtain housing and food assistance. The clinic also helps coordinate care with different health care providers to address different facets of the patient’s health, which they may not have been able to do before.

“These are probably some of the most complex patients we care for,” says Abbey Hardy-Fairbanks, MD, professor of obstetrics and gynecology and a provider in the clinic, adding that one-fourth of their patients don’t have a reliable, working phone. “A lot of them have feelings of distrust for the health care system, so they don’t seek a lot of health care outside of urgent settings or pregnancy. They have a lot of needs that haven’t been met, including mental health and treatment for potential chronic illnesses like hypertension and diabetes.”

Moms-to-be are also prepared for what happens after delivery: care planning, connecting with pediatricians to understand what withdrawal will look like for their babies, planning for what will happen if their baby tests positive for substances, and knowing the role DHS will play once the baby is born.

“It’s about being honest,” says Hardy-Fairbanks. “We try to create transparency and foster trust but also let them know that they’re not bad people, we believe in them as moms, and we can help them create a good, safe plan for motherhood.”

Getting help for substance use disorder and mental health disorders in a clinic setting is often the only option these women have, says Lynch, because many residential treatment programs won’t take them due to their pregnancy or already have long wait lists, and long-term care in a hospital setting isn’t ideal.

“It’s frustrating because they end up sitting in a hospital for a month. It’s not good for them, and it’s not what they need,” she says. “We blame people so much for having this condition, and it’s not fair and it’s not right.”

Collecting data for long-term goals and expansion

Thompson and Hambright hope to form a network with other Midwestern providers also doing similar work.

“I see us being part of a research node and publishing research on what we’re doing and best practices,” Thompson says.

The primary substance used in many states by pregnant women is methamphetamine, she says, which is not as well studied as opioid use among pregnant women. She believes that Iowa and other Midwest clinics can add to the body of knowledge about women with this specific substance use disorder and share their findings widely so that mothers receive the best treatment.

They also want to delve deeper into research on intergenerational trauma and substance use, and what role sexual violence plays in the likelihood of women developing a substance use disorder.

“I want our model to be on a national stage so people can do this where they are, too,” Thompson says.

Iowa saw a 23% increase in opioid-related deaths between 2019 and 2020.

For now, Hambright hopes to expand the program within the university, and find a long-term source of funding. The team’s grant funds the clinic through 2024.

She also wants to change the “implicit bias and stigma against this population,” she says, even from other health care practitioners who may judge these mothers even if they don’t realize it, which can further entrench distrust of the medical community.

“I wish everyone had the opportunity to work in this clinic and see the lived experience of perinatal substance use disorder,” Thompson says. “It’s so easy to make a snap judgement. It’s much harder to do that when you get to know them and see them as human beings and not just someone who is addicted to a substance.”