Table of ContentsClose

Unique bone cancer treatment is customized to each patient’s anatomy

The treatment uses 3D technology to precisely map tumor removal and develop prosthetics that are unique to each patient’s anatomy. It’s helping patients get back to their active lifestyles sooner.

Throughout 2018, Kami Waalkens noticed the pain in her left hip only occasionally. She’d feel a twinge when she worked out on certain machines at the gym, or when she raised a leg to climb into the car, or when she ran a virtual 5K race.

A 25-year-old hospital social worker in Mason City, Iowa, Waalkens ignored the intermittent pain for six months—she assumed her sciatic nerve was acting up—until the day her left leg went completely numb. Soon, doctors uncovered the reason for the ongoing pain: an osteosarcoma had grown in Waalkens’ pelvis, wrapped around her left hip joint.

By January 2019, Waalkens was sitting in the University of Iowa Health Care office of Benjamin Miller (12MS, 03MD) an orthopedic surgeon and the only doctor in the state specializing in orthopedic oncology.

Miller’s initial treatment plan for Waalkens was considered standard practice: surgery to remove the affected segment of the hip joint and replace it with a fitted cadaver bone implant.

But, a few weeks later, Waalkens got a call from Miller suggesting a new treatment option. She was a good candidate, Miller told her, for a new technique that would use 3D technology to create cutting guides customized for Waalkens’ tumor removal and to develop an individualized metal implant that would help boost her post-surgery quality of life.

Waalkens agreed, and the surgery was scheduled for April 2019.

“It really felt like the team at the University of Iowa had my best interests in mind,” she says. “They look out for whatever is best for each patient.”

The UI Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center is the only medical center in the region using this unique 3D application to treat and rehabilitate patients with bone cancer. Though the technology is new, Miller says it is a promising option for not only eradicating and stopping the cancer’s spread but also for improving patients’ function and mobility after surgery.

“Amputations aren’t enough,” he says. “Limbs that don’t work very well are not enough, either.”

Miller, who has used this technique on about half a dozen pelvic reconstructions over the past few years, says it takes into account each patient’s individuality.

“Everybody's anatomy is unique,” he says. “Parts of the bone are unique, as well.”

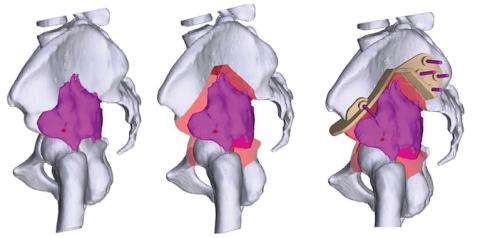

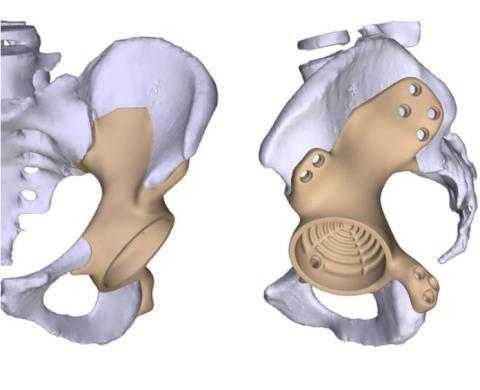

The process begins with a tumor biopsy and imaging scans. Miller uploads the scans to the server of a medical technology company, Onkos Surgical, that creates a 3D model of the surgery site. On a video call, Miller works with the engineers on the specifications of where he will make the cuts during surgery, and these become the basis for the cutting guides. During surgery, Miller places the cutting guide directly on the site to save as much bone and normal tissue as possible during surgery.

“Once you cut a bone,” Miller says, “you can’t uncut it.”

The company also develops a customized metal implant that Miller can insert during surgery after the affected bone segment is removed. Part of the surface of the implant is scoured and treated to help the remaining bone grow into it.

“In the tumor business, we don’t know what we’re going to be left with when we start the operation,” Miller says. “I’ve been reluctant to put a custom prosthesis in because I don’t know exactly how it’s going to fit. But now that we have this ability to plan beforehand, and I have these cutting guides to show exactly the amount of bone that’s being taken out, we can design a custom implant that’s ready to be inserted right when we’re done with the tumor resection.”

Beating cancer, restoring function

Historically in cases like Kami’s, in which the hip joint is cut to remove a pelvic tumor, patients left surgery facing a long recovery and significant dysfunction, such as a shortened leg, that required the use of a mobility assistance device. Waalkens was a great candidate for the new technique because she was young, active, and motivated to beat cancer and restore as much function as possible, Miller says.

“This is a cancer that people survive, but how are we going to make [a patient’s] life as good and meaningful and functional as possible?” he says.

During the six-hour procedure, Miller used the cutting guides before placing Waalkens’ custom metal hip replacement. Waalkens was discharged after a five-day hospital stay. She rested at home, managed her pain, and did some light physical therapy using a walker or crutches. Soon, she started outpatient physical therapy.

“I had a lot of goals to get back to,” Waalkens says. “I wanted to gain as much strength and ability as possible.”

Within three months of surgery, she had ditched the crutches completely and returned to work part time.

Miller says Waalkens’ recovery was typical for patients who are treated with this new technique.

“From [the patient’s] perspective, there still may be some issues,” says Miller, who noted that post-surgery complications can include tumor recurrence, infections, and hip dislocation. “They might limp a little bit, or it just doesn’t feel like a normal hip. But when you compare it to the alternative— using crutches because of a shortened leg and not really feeling stable when you put your leg down on the ground—they’re doing remarkably well.”

Today, Waalkens works full time as an oncology social worker. Her hip sometimes gets sore, especially if she sits or stands for too long. On uncomfortable days, she walks with a slight limp. Jogging causes discomfort, so biking is her new workout of choice.”

I wouldn’t say it’s really changed much of my abilities,” she says. “I am just a bit protective of the hip, though.”

Waalkens sometimes thinks about how her recovery would look different if she had been treated with the standard procedure.

“I don’t have to use a mobility device,” she says. “The fact that there are days that I feel totally normal, and I forget that this prosthetic hip is even in there—that’s the difference.”

Top photo by Liz Martin.

Unique care at Iowa

Benjamin Miller, MD, MS, is the only provider in the region using this 3D application to treat and rehabilitate patients with bone cancer. The orthopedic surgeon specializes in cancer care and limb salvage surgery in sarcoma, metastatic bone disease, and benign bone and soft tissue tumors.