Table of ContentsClose

With sophisticated printers and experts in design and engineering, Protostudios is helping physicians and staff solve unmet health care needs.

Between surgeries, lab meetings, and teachable moments with students and trainees, neurosurgeon Matt Howard, MD, scribbles notes and sketches ideas in his small red notebook.

He’s been doing this over the past 40 years: When he sees an inefficiency in the operating room or grips a surgical tool that doesn’t sit quite right in his hand, he thinks, ‘There has to be a better way to do this.’

These quiet observations and pencil sketches have resulted in more than 30 medical device patents—ranging from brain and spinal cord neuromodulation implants to treat tinnitus, obesity, and chronic pain, to surgical tools and implants that help make surgeries safer and easier to perform.

“My first inventions were as a medical student,” says Howard, who is the chair of the University of Iowa Department of Neurosurgery and the first person in Iowa to be named to the National Academy of Inventors. “My background was in physics, and when I saw some of the ways procedures were being performed, particularly in neurosurgery, it occurred to me that there could be improvements.”

For years, Howard would take his ideas to a machine shop on campus, where skilled machinists could create technical drawings and then build a prototype of the device he was envisioning.

“It was very expensive, takes a really long time to do, and I would use it for five minutes and realize it’s not going to work,” he says. “But you don’t know if the device is going to work until you have a physical version. You can have an idea, but until you’ve actually tested it, you don’t know for sure.”

In recent years, this early development process has been “revolutionized,” Howard says, with the proliferation of 3D printing and, particularly, the establishment of Protostudios—a state-of-the-art, rapid prototyping hub at Iowa.

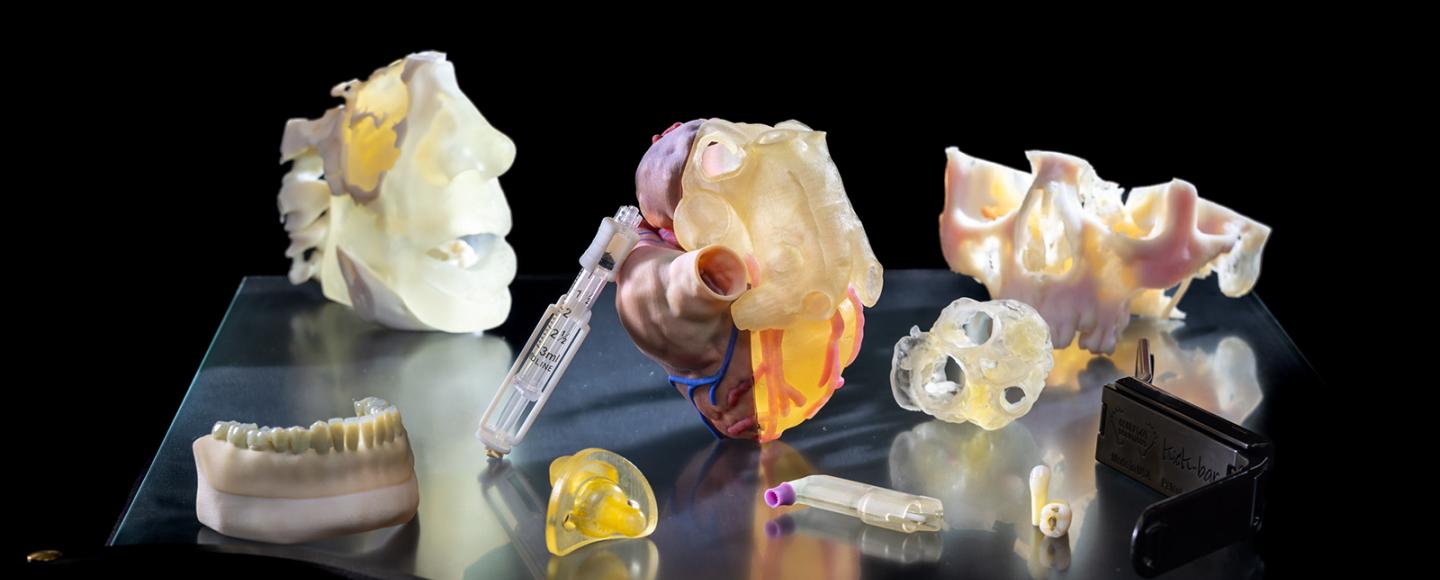

With sophisticated half-million-dollar printers—funded by the Iowa Economic Development Authority—coupled with a team of experts in engineering, 3D design, and manufacturing, Protostudios has established a hub for medical device and advanced surgical tool development on the UI medical campus. It’s also helping faculty and staff improve surgical outcomes and reduce recovery times.

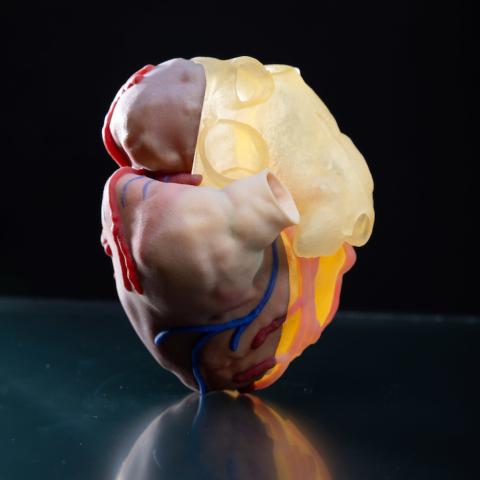

Creating Human Organ Replicas to Improve Surgery Outcomes

Beyond medical device development, surgeons are also using intricate, lifelike 3D models of human organs to prepare for complex surgeries.

“The bottom line is that we’re serving faculty, staff, and trainees with this creative outlet,” says Jon Darsee, the university’s chief innovation officer, who oversees Protostudios.

“It’s all about discovering and addressing unmet needs. If it’s a surgeon, or nurse, or other faculty—people who are motivated to solve problems and see the translation of their research into actual, practical patient care—those are the people we are trying to support. There’s a subset of people here who really have that entrepreneurial zeal.”

Medical and design fields converge

Roughly 70% of the intellectual property created at the UI is related to health care, according to Darsee, and developing surgical tools or other medical devices quickly became the bulk of the work at Protostudios after its inception in 2016.

To help meet the demand, Protostudios recently opened an office inside UI Hospitals & Clinics in addition to its main downtown Iowa City location and machining and fabrication operations on the UI campus.

The expansion to the medical campus has propelled the use of its services even more among physicians and clinical staff. The team currently has active collaborations with faculty and staff in radiology, otolaryngology, urology, neurology, cardiology, obstetrics and gynecology, and the College of Dentistry, among others.

“We never know what we’re going to get when someone walks in,” says Neil Quellhorst, director of prototype engineering with Protostudios. “Sometimes they have pieces of cardboard and wood to try to mock up whatever idea they have. Other times, it’s sketches, and sometimes nothing more than what’s in their head. So, we’ll sit down with them and talk about their profession a bit. Although none of us are medical professionals, we have a fair amount of experience in how to fabricate various things and know a lot about FDA requirements. We all have complementary skills.”

MERGE location on the pedestrian mall in downtown Iowa City.

Designers can refine a sketch, turn it into a 3D computer model, and quickly produce a prototype on the 3D printer. For products that require multiple materials, the team’s workshop is also used for manufacturing and assembly.

“One of the major benefits we offer is really fast turnaround at a reasonable cost. We can convert an idea into a 3D model using a variety of sophisticated CAD [computer-aided design] tools and quickly create a first iteration on the 3D printer,” says Charles Romans, MFA, 3D design director with Protostudios. “It provides a physical 3D object for us to review and discuss the pros and cons further for the next iteration. The goal is to produce a workable prototype to place into the client’s hands for testing and validation.”

Building a proof of concept takes many rounds of trial and error, Romans says, and the speed and efficiency of 3D printing is integral to refining each product before it’s ready for commercial production.

“It’s not uncommon for us to meet between [surgical] operations and look at a prototype, come up with a plan to make it better, and then the next day between operations I’m checking it again,” Howard says. “It's just transformed the process.”

Improved design makes all the difference

In addition to rapid prototyping, the Protostudios team aims to make each product not only functional but ergonomic and aesthetically appealing—with great attention to details such as texture, look, and overall ease of use.

When Chris Cooper, MD, professor of urology, had an idea to better monitor bladder function in children with spina bifida, he turned to the ProtoStudios team to make his device more approachable for young patients.

For patients with this condition, spinal problems may lead to high storage pressure in the bladder, which can lead to kidney damage. The standard treatment includes medications to reduce the pressure and intermittent catheterization. With these interventions in place, a urologist typically follows up annually to monitor pressure levels, but that may not be enough for some patients.

“At some point it dawned on me that this is crazy,” Cooper says. “It would be really nice if these patients could start measuring their bladder pressure at home, and if they started noticing trends of higher pressure—just like with a diabetes patient with higher sugar levels—they could contact me, and we could intervene a lot sooner.”

Cooper’s solution was a device placed on the end of the catheter that works like a tire gauge. The original design was a simple round cylinder with a thumb button used to record the pressure and transmit the data to a phone app.

Although it was functional, the device had several durability issues and wasn’t waterproof.

“I had the idea, but I don’t have this kind of expertise and no experience in device development,” says Cooper, who is also the senior associate dean of medical education in the Carver College of Medicine.

After presenting these issues to the Protostudios team, they immediately started brainstorming plans to improve the design.

“Since the device is used primarily by young children, with assistance from an adult, the approach was to have a look and feel of a gaming controller,” Romans says. “We did this to add some fun into the process, and it would be easier to hold based on the positioning of the hands.”

The new design was based on a Nintendo Nunchuk gaming controller with an index finger trigger mechanism—pulling the trigger instead of pressing a button provides more force for the recording, Romans says. The materials and assembly ensured the inner parts of the device were sealed to improve durability.

“They’ve really been working on getting it to the next step. It snaps together, and they’re designing it with injection molding as a final production process for most of the parts, which will ultimately bring the cost down to several dollars for the casing per unit,” Cooper says. “They're in my own backyard. Literally, it’s three minutes from my office. It's just been phenomenal.”

The team still meets regularly to nail down the design before it can be tested again, but Cooper hopes that it may someday be a tool for standard of care of these patients.

“Folks who want to see their inventions translated into the real world come to realize it takes a wide variety of skills to get to the finish line,” Darsee says of the ProtoStudios design team. “Somebody with an MFA in art is perfectly positioned to support this kind of work.”

Making an impact: Protostudios team refines Iowa clubfoot treatment device

Former University of Iowa physician and pioneering orthopedics specialist Ignacio Ponseti, MD, revolutionized clubfoot treatment with his gentle, nonsurgical approach, called the Ponseti Method. Protostudios is helping take the Iowa brace–created in 2012 to make the treatment experience more comfortable for young patients–to the next level by offering more mobility.

From an idea to improved health care

Protostudios falls into a larger network of resources housed within the UI Office of Innovations, including the Iowa MADE program—an outlet for low-volume, low-risk devices to be manufactured and sold directly from the UI through an FDA-approved process. Iowa MADE and Protostudios often work together to help faculty and staff navigate the process of turning an idea into a product. For some, the goal is to create their own startup companies. Others prefer to patent their idea and license the patent to companies or investors to commercialize.

“With the tech transfer team at the UI Research Foundation, we make connections between the faculty members, industry, and investors, and then we explore the value of what they have externally. Has it been patented before? Are there similar products out there already? We vet these solutions with venture capitalists and industry experts specific to the faculty members' area of interest,” Darsee says.

These perspectives can help reshape and better align the development process, but the end goal typically remains the same: solving an unmet need in health care.

“We’re helping people see what’s possible,” Darsee says. “There are a lot of folks who have ideas for new solutions but don’t feel empowered. We have expertise right down the hall that can help iterate, discuss, and design those elements essential for early-stage development of medical devices.”