Rare cancer care

Treating two girls with the same rare cancer—rhabdomyosarcoma—is more than a coincidence for UI adult and pediatric specialists

Harper Stribe, a 10-year-old from Polk City, Iowa, was just months away from her five-year, cancer-free milestone in September when a routine MRI at University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital detected a suspicious spot at the site of her previous tumor.

The cancer had returned.

“We felt like we were sucker-punched,” says Nicole Stribe, Harper’s mother.

Because this was Harper’s second time with cancer, her pediatric oncologist, David Gordon, MD, PhD—who has been her provider since her diagnosis of rhabdomyosarcoma in 2017—and other UI doctors recommended surgery to remove the tumor from her right jaw joint. The procedure is a standard treatment option for adults with head and neck cancer, but is rarely performed on children. Surgical treatment involved removing the cancerous section of Harper’s jaw and rebuilding it with bone from another part of her body—her fibula.

Faced with this daunting prospect, Nicole Stribe and her husband, Nolan, sought a second opinion on Harper’s case from a renowned medical center out of state. Doctors there echoed the UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital plan.

There were many reasons why the Stribes chose the children's hospital for Harper’s cancer treatment and surgery—including the continuity of care, top-notch providers, and the health system’s long history with this type of surgery. But, for Nolan, the decision came down to another 10-year-old girl: Bella Saul of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Just a few months before Harper’s cancer recurrence was discovered, Bella had faced her own second bout with the disease and had undergone the same surgery at Iowa that doctors recommended for Harper. With both families' permission, the girls and their parents met at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital last fall as the Stribes were determining Harper’s treatment plan.

“Being able to meet Bella and her family was the clincher for me,” Nolan Stribe says. “To see somebody six months after the procedure—full of life and carrying on a conversation and smiling—that, for a dad, was the key.”

Pioneering and adapting a treatment model for pediatric patients

Only about 250 children nationwide are diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma each year. Far fewer face a second bout with cancer—and perhaps just a handful require the type of surgery Harper and Bella needed. Treating two of those cases in the same year at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital might seem like an astonishing coincidence, but the health system has the background, expertise, and collaborative care model necessary to treat this rare pediatric disease.

UI Health Care has a long history of treating adults with head and neck cancers that involve the oral cavity and mandible, or lower jaw. In the early 1980s, the UI otolaryngology department was a pioneer in the successful reconstruction of the jawbone using bone and tissue from elsewhere in the body.

“Since that time, microvascular surgery at University of Iowa otolaryngology has flourished,” says Brian Andrews, MD, a UI otolaryngologist and director of craniofacial reconstruction. “We’ve built upon those techniques.”

Andrews says advances in technology, such as virtual surgical planning, customization of plates and screws, and optics with microscopy, have since made it easier to perform this delicate surgery on children.

“Now we’re able to use those techniques on pediatric patients who present a different problem and unique reconstructive goals,” he says.

A ‘carefully orchestrated’ treatment plan

Andrews, whose expertise includes pediatric reconstructive surgery, was the lead surgeon for both Bella and Harper. Also part of the multidisciplinary care team: attending physicians, resident physicians, fellow physicians, and nurses specializing in pediatric oncology, pediatric intensive care, and speech pathology. Operating room staff from adult units came to UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital during Bella’s surgery to assist the pediatric team in using equipment typically reserved for adult patients. Though each team of specialists has a unique focus, their close collaboration was key to the girls’ treatments.

Like Harper, Bella was originally diagnosed with rhabdomyosarcoma as a young child. In 2015, she was treated with chemotherapy and radiation in Texas, where the Saul family lived at the time. In 2022, UI doctors biopsied a new mass in Bella’s mouth and diagnosed osteosarcoma, or cancer of the bone.

The treatment for osteosarcoma, which is rare in children, typically includes months of chemotherapy, both before and after surgery. Bella’s pediatric oncologist, David Dickens, MD, says care team coordination was essential to streamlining her treatment plan.

“The chemo makes you sick, and your organ systems aren’t top notch, but you have to be well enough to be cleared for a big surgery,” says Dickens, clinical director of pediatric oncology services in the Stead Family Department of Pediatrics. “You have the surgery and recover from the surgery … then you have to time the chemo to start again when the patient has healed enough, but not long enough to let the cancer grow back. It’s a very carefully orchestrated combination of services.”

The surgery itself begins with a tracheostomy procedure, with otolaryngology surgeon Jose Manaligod, MD (95R, 97F), placing a breathing tube in the patient’s neck. The tube is removed before the patient is discharged from the hospital. Next, faculty from the head and neck oncologic surgical services—Kristi Chang, MD (03F), in Bella’s case, and Marisa Buchakjian, MD, PhD (14R, 18R), in Harper’s— remove the tumor and adjacent lymph nodes.

At the same time, Andrews and his surgical team remove an approximately 12-inch section from the middle third of the patient’s fibula bone using computer-engineered cutting jigs for precision. They also harvest skin and soft tissue attached to the fibula, along with its blood supply, to replace the oral tissue and lining that was extracted during the tumor removal.

The removed piece of fibula is contoured and connected to a prefabricated, 3D-printed titanium alloy plate customized to the size and shape of the jawbone that was removed. This new “jaw construct,” made of fibula bone and plate, is anatomically secured to the remaining jawbone. Replacing the piece of fibula that was removed is considered medically unnecessary.

The surgeons’ final task begins with disconnecting the artery and vein supplying blood to the leg tissue. These same artery and veins are transferred to the neck where, with the help of a microscope. This reestablishes the blood supply to the reconstructed jawbone area, providing the patient with new living tissue.

parents Nicole and Nolan during a follow-up appointment in the Otolaryngology Clinic.

Harper’s surgery lasted roughly 14 hours. Bella’s surgery, on her front left jawbone, was slightly shorter because it didn’t include a joint. Both girls spent more than two weeks in the hospital after surgery, including several days in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, where nurses checked the patients hourly to ensure blood was flowing to their new tissue.

“This is a very tricky area in the jaw to remove without causing a lot of abnormal functionality and physical appearance,” Dickens says. “Having Dr. Andrews, who has the experience and training to take a cancer in a very delicate area and offer a patient a good surgical resection, is an absolute key to maximize successful treatment. We can tap into that expertise in rapid fire.”

Finding friendship on the road to recovery

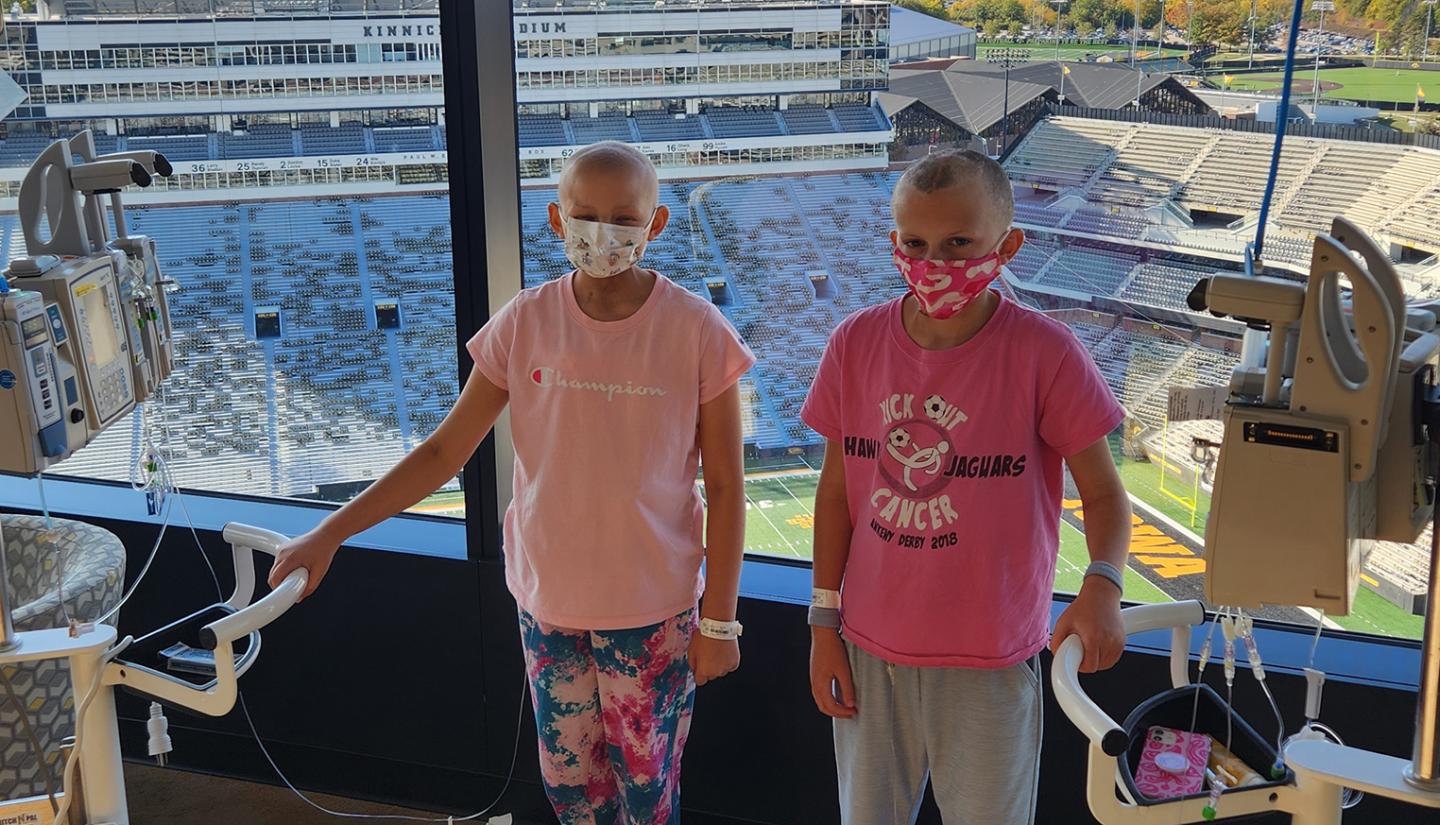

Bella was just six months out of surgery when hospital staff asked if she would be willing to meet Harper. The girls, who turned 11 within a month of each other in fall 2022 and both love basketball and drawing, became fast friends.

“Meeting another person who has been going through the same thing as me is amazing,” Bella says. “The fact that we’re the same age and have a ton in common is even better.”

Bella was there for moral support when Harper decided to shave her head. Harper texted Bella with questions about her upcoming procedure. Bella brought Harper a stuffed animal as a get-well gift after surgery.

“I was really scared at first before I got my surgery,” Bella says. “I really wish that someone would have come and talked to me about it before everything happened. I just didn’t want anyone else to be as scared as I was.”

Harper became emotional when asked about her friendship with Bella, letting her mother give voice to her feelings: “She’s very nice. She understands what you’re going through,” Nicole says to her daughter. “She’s probably one of the few that understand.”

Back on the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, the day after Harper’s surgery, an exhausted Nolan Stribe was on his way back to the hospital from a nearby hotel when he stopped to pick up a soda. Glancing at the newspapers for sale at the store counter, he saw a familiar face on the front page of the Cedar Rapids Gazette. It was Bella, celebrating being back at school full time with her classmates after her cancer treatment.

Nolan, who had been buoyed by Bella’s story before his daughter’s surgery, says seeing the girl’s face that morning was a full-circle moment. He hoped it wouldn’t be long before Harper, too, was back at school, celebrating with her own fifth-grade class.

“With the day after surgery being a pretty low moment for us,” he says, “it was neat to see that.”

Photos by Liz Martin.

Pediatric cancer and blood disease

At University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, children who are diagnosed with cancer have access to the best treatments, including clinical trials of promising new therapies not yet widely available.

Pediatric otolaryngology

UI Stead Family Children's Hospital otolaryngologists diagnose and treat a variety of disorders, including hearing impairment, airway abnormalities, tumors, sinus conditions, and cleft lip and palate.