Table of ContentsClose

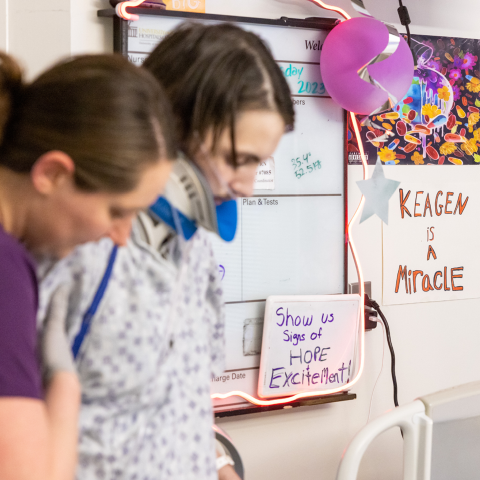

Just a few months before Keagen Kopp walked across the Fairfield High School stage to receive his high school diploma, his mother, Molly Kopp, wondered whether her son would even live to see that day.

On the day before New Year’s Eve 2022, Keagen was pulled from a horrific car accident in Fairfield, Iowa. His mother, who worked nearby, will never forget the scene.

“Every major part of his body was damaged,” Molly Kopp says.

Keagen, then 17, had to be airlifted to University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, the only Level 1 pediatric trauma center in Iowa offering the full range of pediatric critical care therapies.

Keagen would need all the help he could get from a team with the expertise and experience to keep him alive and help him recover. Ultimately, it took nearly every UI subspecialty team, coupled with the highest standard of cardiovascular life support—extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). This is rarely an option for pediatric patients, but UI Health Care is one of a few centers nationally to offer the highest standard of ECMO therapy not only to adults but also to neonates and children.

The big picture

Keagen Kopp is pictured above with his mother, Molly Kopp, four months after his hospitalization. A car crash damaged nearly every major part of Keagen’s body, requiring him to spend more than 68 days on life support with nearly every UI subspecialty team involved in his care.

All hands on deck for a complex medical case

When the children’s hospital trauma team assessed Keagen’s many injuries, the worst included multiple spine, rib, and breastbone fractures; internal bleeding in his chest, lungs, and stomach; additional injuries to his lungs, liver, spleen, kidney, and pancreas; and possible brain trauma.

Keagen was completely unresponsive, even to pain, says Aditya Badheka, MBBS, MS (15F), medical director of the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

“It was touch-and-go several times,” he says.

Facing so many disparate injuries and quickly evolving, life-threatening conditions, the PICU team members found themselves “standing in the eye of a storm,” Badheka says.

Around them circled the other specialists that would help Keagen.

“That’s the beauty of having all the subspecialty teams at the University of Iowa, where you can call the experts anytime of day or night,” Badheka says. “It’s wonderful to work in a place where you find all of this under the same roof.”

Unexpected complications arise

One by one, the pediatric trauma and specialty teams triaged Keagen’s many injuries. Neurosurgery determined that Keagen’s spinal fracture could be managed conservatively. His brain trauma, which didn’t appear severe but couldn’t be fully assessed until Keagen was awake, would have to wait. While evaluating his internal bleeding, doctors discovered that Keagen had developed a pseudoaneurysm—a leaking blood vessel that caused an artery near his heart to balloon with blood. If the artery burst, Keagen could bleed to death.

“It’s like a ticking time bomb,” Badheka says.

In collaboration with the interventional radiology team, vascular surgeons operated on Keagen to address the pseudoaneurysm, inserting a stent to keep the artery from growing any larger.

Then Keagen developed a bloodstream infection.

“That was our first major setback in his care,” Badheka says.

The next, and more concerning, obstacle came about 10 days into Keagen’s hospitalization, when he developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Fluid had accumulated in Keagen’s lungs, making it too difficult for him to get a full breath, even on a ventilator. Keagen’s lungs were failing, and his care team determined that he needed the maximum amount of support they could provide. The intervention is ECMO—a high-risk form of life support that would take over Keagen’s lung function, effectively keeping him alive in the hopes that his lungs would rest and repair.

An international leader in ECMO

To put a patient on ECMO, a surgical team first places cannulas. Blood from the vein is diverted from the body to the ECMO machine, which sits on a cart at the patient’s bedside. The machine circulates the patient’s blood, adding oxygen and removing carbon dioxide, just as healthy lungs would. The oxygenated blood is then transferred back through the cannula and into the vein.

The Stead Family Department of Pediatrics has about 20 ECMO cases a year, says Sarah Haskell, DO (08R, 11F), critical care division director, including patients with heart failure.

“Several years ago, doctors didn’t even consider ECMO for trauma patients like Keagen,” she says. “It is something we still don’t do a lot of in these polytrauma cases.”

The increased risk of bleeding on ECMO has been a factor in its limited use in pediatric patients, but with the improvement of technology and expertise, it is now considered a treatment option for select cases, such as Keagen’s.

An international leader in ECMO, UI Health Care is among approximately 30 health systems worldwide to receive the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) Award for Excellence in Life Support–Platinum Level. UI Health Care’s ECMO experts train medical professionals around the globe on how to use this life support system.

Still, Keagen’s doctors were clear with Molly Kopp: ECMO was not a cure. Her son’s lungs would eventually need to heal enough on their own for Keagen to come off life support. Plus, ECMO carried its own set of risks, including bleeding, infection, and blood clots.

“The longer we stay on ECMO,” Badheka says, “the more complications we get.”

Keagen went on ECMO on Jan.10, and the care coordination by his medical team went into overdrive. While on ECMO, Keagen also remained on the ventilator. A patient on ECMO is treated by the entire ICU team as well as a specialized ECMO team that includes respiratory therapists.

A trained ECMO specialist remains by the patient’s bedside around the clock to monitor the ECMO machine and ensure it is functioning properly, says Cody Tigges, DO, a pediatric critical care specialist.

“It’s a high resource utilization mode of support,” he says.

Yet for six weeks on ECMO, Tigges says, Keagen’s lungs “essentially made no progress.”

A recovery that's 'beyond belief'

Molly Kopp found those weeks of Keagen’s hospitalization particularly harrowing. Loved ones tried to encourage her by noting that Keagen must be recovering since he was in the hospital.

But “that’s not at all what was happening,” she says. “They’re keeping him alive.”

Worried that her son’s lungs would not recover, Molly Kopp approached Keagen’s care team with a difficult question: What about a lung transplant?

UI Health Care does not have a pediatric lung transplant program. But Keagen by then was just a few weeks shy of his 18th birthday, and he was out of options.

The pediatric team agreed to call their adult lung transplant colleagues at UI Hospitals & Clinics—home to Iowa’s only lung transplant program—to ask them to evaluate Keagen for a possible transplant.

“It was an uncommon collaboration,” Haskell says. But, she adds, “The children’s and adult hospitals are in such close proximity that you really can work together and do everything within that same center.”

The adult lung transplant team performed an initial assessment—consulting with the pediatric care team and reviewing Keagen’s medical records—and determined they would need to address several medical issues, including a lung infection, before a transplant could be considered, says Julia Klesney-Tait, MD, PhD, a pulmonologist and medical director of lung transplantation.

“In the state that he was,” she says, “transplant wasn’t an option.”

On Feb. 24, Keagen underwent a 12-hour, multipart operation to tackle the issues one by one. Evgeny Arshava, MD (08R, 13F,16F), a cardiothoracic surgeon, performed a thoracotomy to drain infection and remove scar tissue from Keagen’s right lung, while the interventional radiology team inserted drains to clear the other side. Doctors from pediatric otolaryngology stemmed the nasal bleeding caused by Keagen’s feeding tube; the tube was later replaced by a feeding tube in the stomach.

To remove the breathing tube from Keagen’s mouth, otolaryngology surgeon Jose Manaligod, MD (95R, 97F), performed a tracheostomy. Cardiac surgeons changed Keagen’s ECMO configuration by removing the cannulas from his lower body and placing them in his neck. The anesthesiology team provided support throughout the surgery.

“We had five different teams in the operating room that day,” Klesney-Tait says. “Tremendous collaboration was necessary between so many different subspecialties to get him through this. It was really a full team effort to figure out a way out of it for this kid.”

With the tubes removed from Keagen’s nose and mouth, doctors began to wean him off sedation, slowly waking him for the first time in his hospitalization, says Mark Pedersen (08MPH, 14MD, 18F) an anesthesiologist and an adult ECMO managing physician.

“We wanted to get him more awake and alert and interactive,” he says, “so he could start the rehabilitation process.”

Keagen began physical therapy, starting with passive range-of-motion movements like flexing and extending his arms and legs. Meanwhile, with his lungs surgically cleared, Keagen’s breathing and chest X-rays began to visibly improve.

“We slowly increased the ventilator support and decreased the ECMO circuit support,” Klesney-Tait says. “We realized we’d hit an inflection point. His lungs are getting better, and we’re going to be able to get off ECMO.”

After 68 days on life support, Keagen was taken off ECMO on March 18.

On his 18th birthday a week later, Keagen left his hospital room for the first time, taking a spin around the halls in a wheelchair.

“The timing happened so perfectly,” Molly Kopp says. “Pediatrics kept him alive. He needed that time in pediatrics. Then we got to transfer over to the adult side, and that’s when things really started moving.”

Once off ECMO, Keagen was transferred to the Respiratory Specialty and Comprehensive Care Unit, where he could continue physical therapy and occupational therapy until he was well enough to leave the hospital. Keagen remained on the ventilator for another couple of weeks until doctors determined what everyone had hoped: He wouldn’t need the lung transplant after all. After 101 days in the hospital, Keagen was discharged to St. Luke’s Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in Cedar Rapids on April 10.

Soon, Keagen was taking his first unassisted steps post-crash, and Molly Kopp was sharing the videos with her son’s pediatric team.

“Keagen had slim chances of staying alive after the accident,” Badheka says. “He not only made it out of this alive against all odds, but also with no major disability. It is beyond belief.”

By the time he graduated from high school, Keagen could walk short distances unsupported. He’s gaining energy and stamina every day, Molly Kopp says, and is looking forward to being strong enough to beat his friends at arm-wrestling again.

In June, Keagen had surgery to treat a small bowel obstruction, and he will continue to follow up with his UI Health Care doctors, his mother says, and maybe even feel well enough for a part-time job by then.

“I will never not believe in a full recovery,” Molly Kopp says.