Table of ContentsClose

Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) are a leading cause of death and disability in children and adolescents in the U.S. In fact, infants up to age 4 and teens between the ages of 15 and 19 are at greatest risk for a brain injury, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

While advances in pediatric critical care in the past two decades have led to greatly improved survival rates in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) nationally, neurological dysfunction is still a common result of critical illness, particularly after TBI.

That’s what makes Elizabeth Newell’s research on TBI so important.

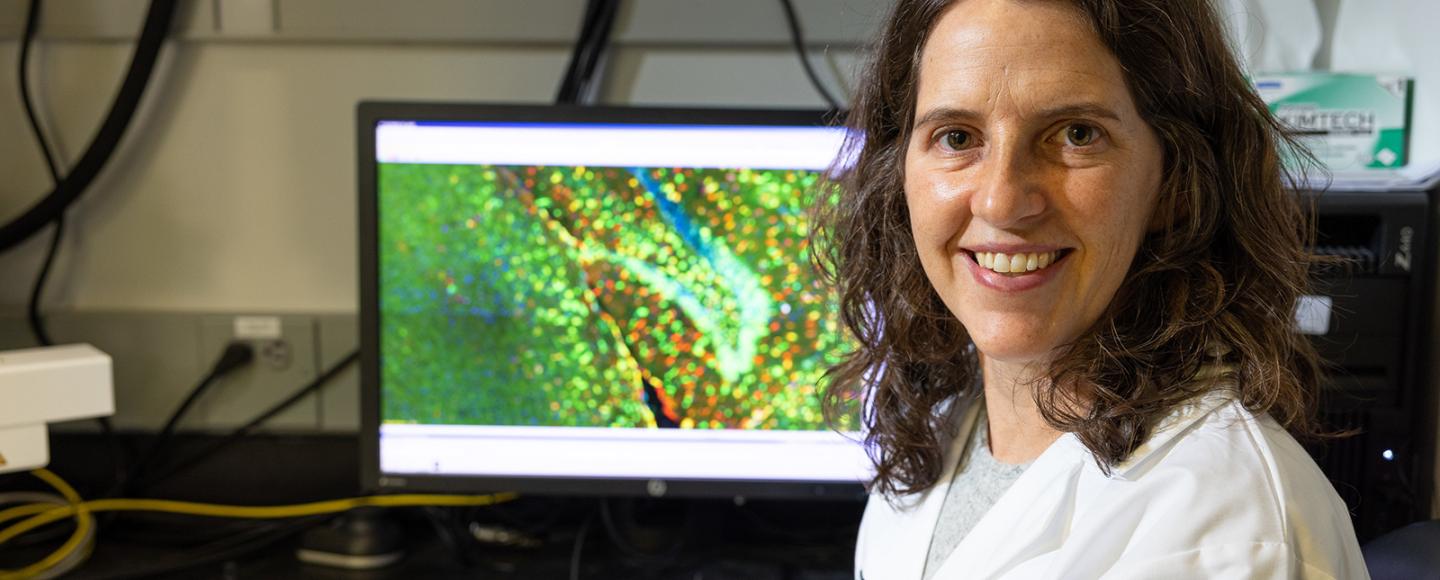

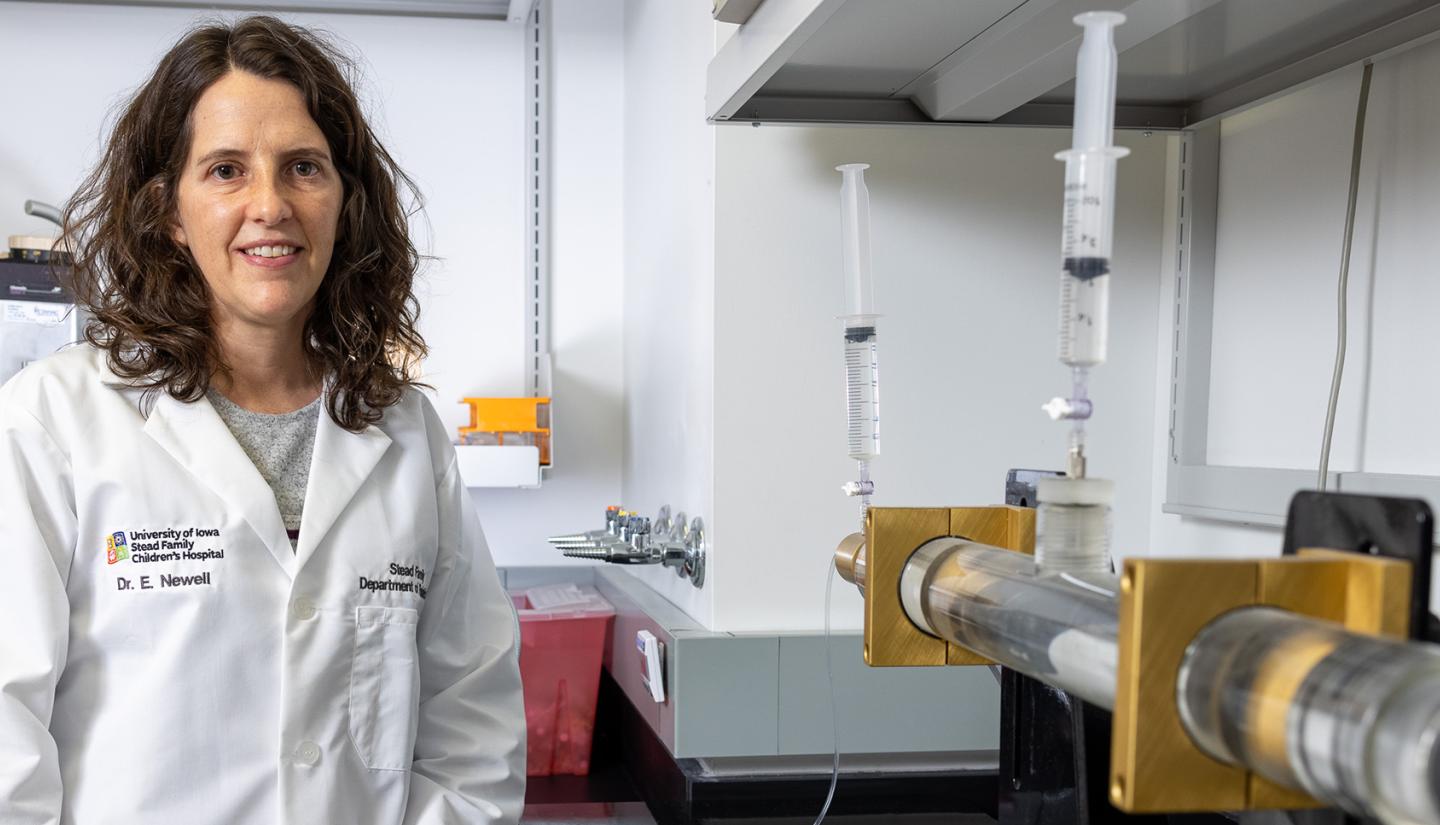

Newell (05MD, 08R), an assistant professor of pediatrics–critical care in the University of Iowa Stead Family Department of Pediatrics, is working to improve outcomes following TBI in her clinical care practice, which she couples with her research on how immune cells in the brain respond to a TBI and impact long-term recovery.

Although neuroimmune activation is crucial to recovery after TBI, a dysregulated immune response can result in secondary brain injury. One area of Newell’s research focuses on how neuroinflammation contributes to these long-term deficits after a TBI, which can continue for months or years following the immediate impact.

“Those are the pathways where there’s opportunity to intervene because there’s a prolonged therapeutic window,” Newell says. “That’s our focus.”

A pathway for intervention

A unique aspect of the brain is its limited regenerative cell capacity, she explains. This means that when cells immediately die at the time of trauma, there are currently no interventions that can repair that cell loss. When secondary injury pathways are triggered, cell death can continue to happen, but medical providers can step in and interrupt further neurological degeneration for their patients.

This is where the work of Newell’s lab comes in—by identifying the molecular mechanisms of TBI, the lab aims to target them for new and precise therapies.

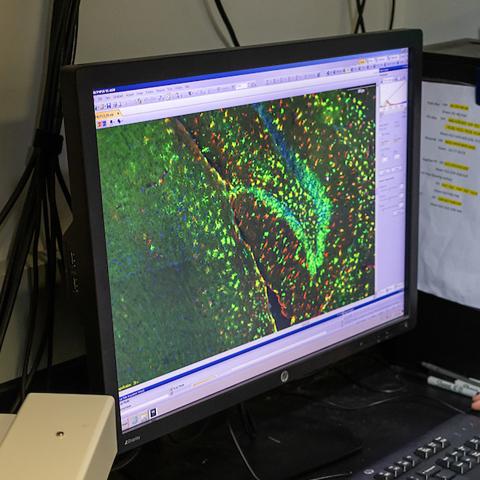

Her lab has used novel techniques to evaluate the molecular responses of specific cell types to TBI. In a 2021 study published in the Journal of Neuroinflammation evaluating the effects of TBI on sustained gene expression changes in microglia—the primary immune cell in the brain—they discovered that type I interferon responsive genes accounted for a large number of the gene expression changes that occurred. Type I interferons are proteins that regulate the recruitment and effector functions of immune cells and are well known for their role in clearing viral infections. They have received limited study in TBI, however, and their role in chronic neurodegeneration following TBI is unknown, Newell says. This is an area the Newell lab continues to actively study and Newell has submitted a proposal to the National Institutes of Health for support of this ongoing work.

The lab also developed a novel pediatric rodent TBI model to facilitate the study of age-dependent effects of neuroinflammation following severe TBI. As a pediatric intensivist, Newell is passionate about improving outcomes for her patients through translational research.

A supportive environment for a physician scientist

The inspiration for Newell’s line of research began during her fellowship training in the PICU at the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, where she was mentored by leaders in the fields of brain trauma and resuscitation.

“That was when I cemented my plans to do brain injury research and tie in my initial interest in studying the immune system and inflammation,” she says, adding that neurological disease is the leading cause for care in the PICU. “There’s been great advancement in our field, but I think the brain and neurological function is still an area that’s in need of further advancement. The brain is key to who we are and what we do.”

Newell, who earned her MD from the Carver College of Medicine and completed her pediatrics residency training at UI Stead Family Children’s Hospital, became a faculty member in 2012 after her fellowship training in Pittsburgh.

The opportunity to bring the TBI work she began as a fellow into her lab as a faculty member excited her, and she remembers feeling eager to return to the department because it has a strong history of supporting junior investigators and physician-scientists.

“I found that very much to be true, and I received great mentorship and support from a number of people in the department and the department overall,” Newell says.

She’s now able to maintain a healthy mix of lab work and her role as a physician, too, and thinks the work she does in each role allows her to best contribute to improving the health of children.

“In the PICU, the work can be intense. We have long hours, and it’s physically, mentally, and emotionally exhausting,” Newell says. “But then the lab brings a balance in terms of being able to step away from that intensity and answer questions that are critical at the bedside for the patients we’re caring for.

“I’m better at what I do in the unit, and I’m better at what I do in the lab because I do both those things,” she adds.

Photos by Liz Martin.

Traumatic brain injury research

The Newell Lab studies how neuroinflammation contributes to TBI so that novel targeted therapies may be developed.