Table of ContentsClose

An out-of-body experience. That’s how Cody Purvis describes losing nearly 75% of the hair on her head as a result of the autoimmune disease alopecia areata.

“The person that I looked at in the mirror every day was just not who I was,” says Purvis, a pet boarding and grooming business owner in Kanawha, Iowa.

In alopecia areata, the body’s immune system attacks hair follicles. It can result in small clusters of hair loss or a total loss of body hair—including eyelashes and eyebrows. And the condition is common: More than 300,000 people in the U.S. develop a severe form of alopecia areata each year, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Prior to the last decade, patients with this emotionally tolling disease had few treatment options to find relief. Luckily, recent advancements have completely changed the landscape of therapies, due in part to the research prowess of dermatologists like Ali Jabbari (07MD, 07PhD).

Jabbari, associate professor and chair of the University of Iowa Department of Dermatology, has become an expert on alopecia areata, both in the lab—where he’s working to target the autoimmune processes that cause hair loss—and in the UI Hair Loss Disorders Clinic he started in 2017. Coupling his research with his clinical care is leading to better outcomes for patients and a pathway back to their identities.

Autoimmune drug becomes a go-to treatment

Finding the right treatment for Purvis and other patients has been the target of Jabbari’s research since his days as a trainee. While completing his postdoctoral training at Columbia University Medical Center, Jabbari joined the lab of Angela Christiano, PhD. They set out to characterize alopecia areata from an immunological standpoint and ultimately created a preclinical rationale for repurposing JAK inhibitors—a drug used to reduce the inflammation in autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis—for alopecia areata.

“We had a mouse model of the disease where we did our mechanistic work, and then we started using JAK inhibitors in patients,” Jabbari says. “Patients who were formerly bald started growing hair like gangbusters, so that led to some really striking photographs and a big, splashy publication for the lab.”

Jabbari was one of the lead investigators on the landmark study, published August 2014 in Nature Medicine. As a result, JAK inhibitors have quickly become a go-to treatment for patients with severe alopecia areata.

Jabbari later returned to Iowa—he graduated from the Carver College of Medicine Medical Scientist Training Program in 2007—to continue studying the condition while also starting his clinical practice.

“When I came back, I had a dance card full of hair loss disorder patients,” he says. “I feel like I've developed a certain level of clinical expertise with regard to these patients.”

Jabbari also set up a site for two Pfizer JAK inhibitor drug trials for alopecia areata, joining roughly 50 testing sites worldwide and giving patients in Iowa new access to treatments.

The FDA approved the first JAK inhibitor—called baricitinib—for alopecia areata in June 2022, with a second JAK inhibitor—ritlecitinib—approved in June 2023, which will be available to adults and children 12 and older.

The emotional toll of severe hair loss

Purvis was first diagnosed with alopecia areata when she was in seventh grade.

“My cousin was blow-drying my hair and she said, ‘Oh my gosh, you have a big bald spot back here,’" Purvis recalls.

At the time—nearly 20 years ago—the only treatment option she was given was a topical ointment for the affected spot, which proved to be ineffective for Purvis. So, throughout junior and high school, she had a coin-sized bald spot that would migrate around her head. She covered it by readjusting her hairstyles.

A decade later, after her second child was born, Purvis started losing more and more hair, until nearly all the hair on her head was missing. She decided to shave off the rest in November 2017.

Once proud and confident in her long, brown mane, she now started noticing people’s curious, even concerned, looks at the grocery store. “People would ask if I had cancer,” she says. “That was the hardest part, because I didn't want people to think I was sick. There are people who are fighting true battles with cancer. I really struggled with that because I'm like, ‘Don't give me that sympathy.’”

But the condition did take its toll.

“Not having my hair was really hard on me emotionally,” she says. “It's surprising how much head hair makes you feel like yourself.”

Purvis’s Fort Dodge doctor didn’t have many treatment options left for her to try, so he referred her to Jabbari.

She was relieved to learn that Jabbari immediately had a treatment plan, and she started taking a JAK inhibitor called tofacitinib, or Xeljanz.

“I was on the medicine for roughly four years, and now my hair is back to 100% normal.”

After losing much of her hair as a result of alopecia areata, Cody Purvis shaved her head in November 2017. Once she was referred to the UI Hair Loss Disorders Clinic, she was relieved to learn Ali Jabbari, MD, PhD, had a treatment plan which included taking a JAK inhibitor called tofacitinib, or Xeljanz. Her hair is now back to its full length and thickness. Photos courtesy of Cody Purvis.

Purvis now has hair that’s halfway down her back, and it’s grown back with the same fullness she was once proud of.

“Dr. Jabbari was the first person who actually gave me hope,” she says. “He was the first person who found a solution that worked for me and made me feel back to who I was. He brought my old self back.”

Since this drug is not FDA-approved for alopecia areata, it took persistent appeals by her UI Health Care team to get the treatment covered by insurance. This year, the drug was not approved by insurance, and Purvis had to stop taking it. Fortunately, she hasn’t noticed any additional hair loss since stopping the medication.

Purvis continues to see Jabbari for maintenance—which sometimes includes steroid injections to her scalp—and she feels comforted knowing that if she started losing her hair again, several new drugs are now approved by the FDA, which will help patients receive insurance coverage.

T-cells focus of new research on targeted therapies

Although the application of JAK inhibitors to treat alopecia areata was a major stepping stone in the field and for patients like Purvis, Jabbari’s lab is looking ahead at other, more targeted treatment approaches, shifting the focus away from broad-acting immunosuppressants.

“JAK inhibitors have been working fantastically, but they're not going to be the whole story because not everybody responds to JAK inhibitors,” he says.

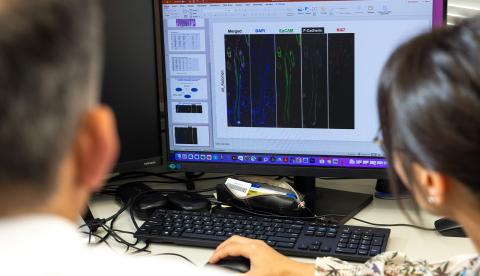

Jabbari’s lab is looking at the role of regulatory T-cells in alopecia areata, specifically enhancing their function or quantity to see whether it has an effect in a mouse model of the condition.

The lab is now working on a proof-of-principle study focused on a newly discovered cytokine, called IL-27, which has shown great success in preventing the onset of the disease.

“We found through a collaboration with a faculty member, Xue-Feng Bai, at Ohio State that if we overexpress IL-27 in our mouse model, the mice never go on to develop disease,” Jabbari says. “When we induce disease in mice, nearly 100% of our mice get it, but if we give them this IL-27 through a viral delivery method and then induce disease, none of those mice go on to develop disease.”

This method might be working by increasing and activating the regulatory T-cell compartment in the mice, Jabbari adds. The lab hopes to optimize this finding to reverse established disease, creating the potential for a new therapeutic approach.

“JAK inhibitors are having their time in the spotlight, and rightfully so, but we will continue expanding our knowledge of the disease process so that we can come up with new therapeutic strategies,” Jabbari says.

Photos by Liz Martin.

The Jabbari Lab continues to study the disease progression of alopecia areata in order to find more targeted treatment approaches.