Table of ContentsClose

The full picture

From painting to poetry to podcasting, the Carver College of Medicine Writing and Humanities Program nurtures a new generation of well-rounded physicians.

The Greek god Apollo was the god of medicine, art, poetry, and music. Following that model, physicians for centuries married the science of medicine with the arts and humanities.

“Once upon a time, physicians were expected to be well-read representatives of society. They were the artists and philosophers,” says Mgbechi Erondu (17MD), University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine alumna and now an anesthesiology resident at Baylor College of Medicine.

An overhaul of U.S. medical education in the early 1900s established scientific knowledge as the defining attribute of the modern physician, leaving little room for the arts and humanities. However, in recent years many medical schools have been rediscovering their benefits—including helping physicians develop the capacity to listen, interpret, and communicate with patients, as well as maintain a better work-life balance.

The Carver College of Medicine was an early adopter, developing its Writing and Humanities Program in 2001—and taking advantage of the strong writing, arts, and humanities resources already on the UI campus. The program focuses on the humanistic and artistic dimensions of medical education and practice. It offers elective courses and arts and humanities activities for medical students; administers the Humanities Distinction Track; produces The Examined Life Journal and “The Short Coat Podcast;” and hosts the annual Examined Life Conference.

Cultivating communication skills

Cate Dicharry, MFA, director of the Writing and Humanities Program, says the skills students gain directly impact their medical education, helping them to absorb and interpret what patients are experiencing.

“They go into an exam room as a whole person with stories, and they interact with someone who has a whole lifetime of stories and experiences,” Dicharry says. “Assumptions will be made about each other, and they have to find ways to communicate. Thinking through the elements of storytelling—whether it’s through literature or creative writing—is one way to make those tools available and to practice them.”

Erondu, who graduated with an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 2016 before earning an MD degree at Iowa, agrees.

“How do you listen, really listen, to a patient?” Erondu says. “The best way to do that, I think, is to be a good reader. And not just reading textbooks, but fiction. Because when you read fiction, you’re forced to imagine things that are in another world. And how you interpret it might be different from how the author intended, and that’s OK. You don’t have to worry so much about the right answer. Being willing to be wrong or surprised, those are all things that are developed in people who are invested in the humanities.”

Effective communication with patients also is a skill that medical students are expected to develop, but isn’t always addressed in a formal medical school curriculum. “The Short Coat Podcast”—in which med students discuss the current events, social aspects, and people of the medical field—offers one opportunity for students to communicate with a broader public.

“The podcast lets them practice talking about concepts they are learning,” says David Etler, administrative services coordinator in the college’s Office of Student Affairs and Curriculum and co-host of the podcast. “I act as the naive listener because that’s what I am. They are forced to avoid jargon when explaining things to me. It’s important not to speak to people in the wrong language.”

Short Coat Podcast

What’s it like to be a medical student? Since 2010, the students at the University of Iowa's Carver College of Medicine have chipped away at that question. Learn more about what they don't tell you about med school, but should.

Third- and fourth-year students also can take an improv class taught through the UI Department of Theatre Arts to help them learn to think on their feet and prepare for the unexpected conversations they’ll face every day as physicians.

Erondu, who worked on a novel while in the Humanities Distinction Track, says she always knew writing was essential to who she was. And while she says she didn’t participate in the Writing and Humanities Program to pad her résumé, she found that it made her a unique candidate on the interview trail.

“I was rarely asked about anything medical,” Erondu says. “I was asked about my writing, my novel, my MFA. They were interested in my point of view. I think it sets you apart from the average applicant.”

Creative outlets

While the Writing and Humanities Program prepares medical students for their professional lives, it also impacts their personal lives. High-quality health care requires the well-being and health of medical professionals, yet the National Academy of Medicine estimates that half of American physicians experience burnout.

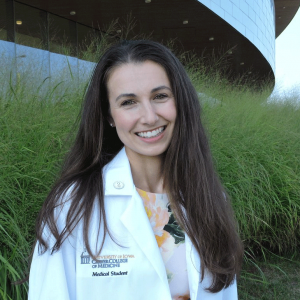

Claire Castaneda, a third-year medical student from Dubuque, Iowa, says participating in the Writing and Humanities Program through “The Short Coat Podcast” and working on a collection of short stories as part of the Humanities Distinction Track have proven invaluable to her medical school experience.

“If med school was my whole life all the time, I would burn out. It would be a supernova,” Castaneda says. “As much as I love medicine, you can love a lot of things but also not love them every day.”

Given that medical professionals are entrusted with the lives of others, and they often bear witness to the toll that disease and trauma take on people, Castaneda says it’s helpful to have an outlet in which to express herself.

“Sometimes you have so much coming at you, and there are things, such as death and tragedy, that you know other people don’t often see,” Castaneda says. “You need somewhere to put it all sometimes.”

Many students pursued interests in writing, the arts, or humanities before they decided to go to medical school.

“We want students to know that you don’t have to give up your interests to become a physician,” Etler says. “In fact, you absolutely should not do that. I always say you’ll be boring if you do that. And exhausted.”

Dicharry says she knows it can be hard to fit in such activities around the demands of medical school, but the Writing and Humanities Program can help.

“It gives students a formal structure in which to pursue those interests,” Dicharry says.

Students currently pursuing the Humanities Distinction Track are working on a variety of projects: visual artists working on paintings, fiction writers and poets putting together manuscripts, a musician composing a concept album rooted in his medical studies, and a student who is taking a more academic approach by looking at health care access for young women who are addicted to opioids.

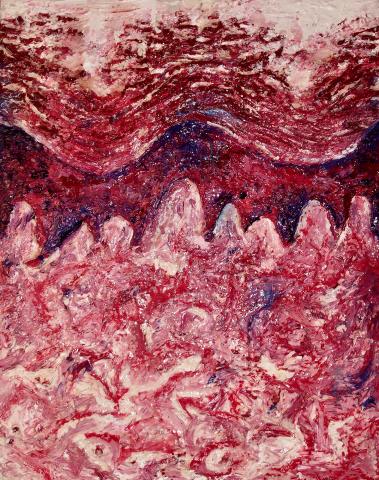

Third-year medical student Maggie Gannon’s paintings interpret histology slides in an effort to capture both concrete and abstract elements of medicine—the pathology and the people behind it.

“I have spent many hours as a medical student learning the hard truths, laws, and rules that provide the framework for clinical decision-making,” she says. “However, I was surprised to see that practicing medicine in the wards is far less absolute than what was written in my books.”

This painting is titled, “H&E Stain of Thick Skin; Dermis and Epidermis.”

"La Verdad" was inspired by an experience second-year medical student Liana Meffert had at a volunteer medical clinic.

“What struck me about this interaction was the level of trust this patient put in us, as exemplified during the physical exam,” Meffert says. “It's not uncommon for free medical clinics to receive undocumented workers. Given the current political milieu, this interaction was especially potent. It made me wonder about how our political climate will shape my future practice, and if I will always feel my hands are tied behind my back, even for those who need it most.”

The poem was originally published in the American Medical Women’s Association literary magazine.

La Verdad

There’s no translator I can find to explain

in a language that’s been curdling

my tongue like it’s never known

my name

why being sick

doesn't mean you get help

from those that can give it—

these scraps of speech pieced together

like magazine clippings for a ransom letter

to your body this is what

your surgery will cost

which is just a number, really, meaning more

imaginary things—

I watch the corners of your eyes crinkle

when we talk about your wife

your hands spread wide

to show just how much you can carry,

the careful stich of callouses across palms.

So when you unbutton your pants without pause

to show me where it hurts

your trust exposed in the relief of

leafy green office plants & quickly

shrinking in the ventilated air

it is me exposed

with this zipper on my lips:

this summer with no escaping

what the Rio Grande can swallow

& nothing to be promised.

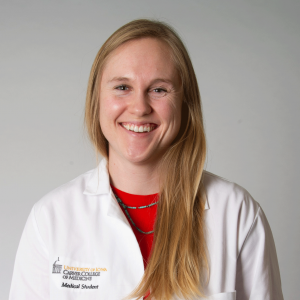

Second-year medical student Emily Parker is exploring whether her medical school experiences shape her paintings—the colors, the themes, or the frequency of her practice.

To delve into possible connections between art creation and the stages of medical school, Parker is creating an annotated art portfolio that combines monthly paintings with journal entries, along with brief reflections on each combination.

“I enjoy [making art] because I get tangible results,” Parker says. “At the end of four hours of studying, my yield is just checking an item off the to-do list. But at the end of four hours of painting, I can have a completed canvas to show for it.”

This painting is titled “Marbled Chemistry.” It was inspired by the visual appeal of blending the abstract and the geometric; in this case the measured hexagons combined with the freehand gray and golden veined marble background.

Third-year medical student Jane Persons is writing an extended personal narrative to explore her identity as an individual and soon-to-be physician. Her goal is to use the practice of metacognition—the awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes—to gather new insights and, in turn, improve her ability to manage emotions and stress while also expanding her ability to communicate, understand, and empathize with others.

Persons designates one hour a week for silent self-reflection, followed by a written reflection. The final product will be an extended personal narrative—a year of weekly written reflection compiled chronologically into a single volume.

“Regardless of the direction my exploration may take, my writing will serve as an open and honest narrative, laying bare my discoveries as they occur,” Persons says.

June 9th, 2018 (Saturday)

I take for granted that I have human contact in my life on a daily basis. People to speak gently with, to share stories and ideas with, to educate and to learn from. People to share touch with, to nurture, to hug and snuggle. Even people just to hear breathing in the night, to see evidence of their existence in my life. Shoes on my shoe rack, notes in their handwriting. To know that I have people to reach out to, to draw in close to me if I was in need of closeness. And yet, I am grateful too that I am able to retreat into my own space to think and recharge. All things in balance.

July 14th, 2018 (Saturday)

Today I am thinking about adaptation and how easy it can be to smoothly transition from one way of being to another, now readily one can forget how things used to be. I got LASIK a few days ago. I don’t wear glasses anymore after twenty years of wearing glasses all day every day, and already it feels as though I never wore them in the first place. It makes me wonder how many other things I have gradually gotten used to, how many things I have over time forgotten used to be better—or worse. How much have I changed without even realizing?

November 4th, 2018 (Sunday)

For lots of years now, I feel like I have been building something—building my professional self—without realizing knowing quite what the finished product will be or how everything will fit together. I stubbornly refuse choosing an end goal and forcing myself to fit cleanly into that preset design—too many important edges and contours have to be worn away to make the fit. People can be two things, but eventually it all cooks down together into one excellent new thing. I’ve been thinking about something A-- said a few years ago, that sometimes people overcome like a wrecking ball overcomes a building, and sometimes people overcome like a fungus overcomes a tree. This is me overcoming like a fungus, growing a new something one small move at a time, destroying an old something as I progress.

Should doctors practice what they preach? Third-year medical student Annee Rempel is tackling that question in an effort to better understand whether physicians and trainees have a professional responsibility to lead healthy lives. Her distinction track project posed this question to Carver College of Medicine students, and the results may have implications regarding physician burnout and wellness curricula.

Rempel kicked off the project with a summer bike tour from upstate New York to Iowa City after her first year of medical school. She completed the three-week trip with her mother and UI Carver College of Medicine alumna Jean Linder (78MD).

“It was my goal to better understand how practicing physicians balance personal wellness with patient care,” she says, adding that she chose to interview physicians by bike because the ability to travel long distances by bicycle is part of her personal notion of health.

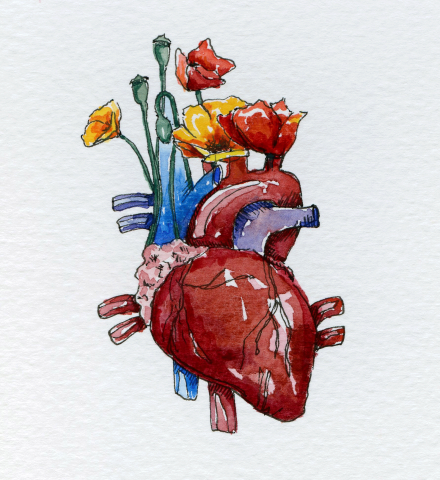

Rempel chronicled the 936-mile trip in an online blog and painted this heart as an emblem. The original image is intricate and roughly the size of a business card.

Fostering a culture of medicine and humanities

As more medical schools begin to put a focus on the arts and humanities, the Carver College of Medicine stands out in that its Writing and Humanities Program is run not by a medical professional, but a writer. Erondu and Castaneda both say that when deciding where to go to medical school, they looked for one that put an emphasis on the arts and humanities.

“Not a lot of medical schools have an opportunity like you find at Iowa,” Erondu says. “Even if you’re not necessarily interested in these programs, the fact that they are offered is really important. It speaks to the culture of a place.”

Castaneda says she appreciates the time and space given to explore non-medical interests.

“So many of my classmates have gifts and talents they want to nurture,” Castaneda says. “I’ve met a few who are beautiful artists and others who try their hand at poetry and absolutely crush it. It’s refreshing to see people still taking those risks because I think it can sometimes be hard in this environment to try something new and creative. It’s good to know people are willing to push their comfort zones and continue expanding who they think they are, and not just say, ‘I’m this now and only this.’”

Erondu agrees.

“Just like in the way they tell you to be open to different medical specialties, I feel everyone should be open to different ways of thinking and learning from unexpected places, like a work of fiction, a painting, a poem.”

While participation in any Writing and Humanities Program class or activity is voluntary, Dicharry hopes that soon every medical student will interact with elements of it at least once during their time at Iowa. She works with faculty to add elements of writing and humanities to required classes.

“This program speaks to students’ humanity and not just their clinical side,” Dicharry says. “There’s a reason why a lot of med schools are moving in this direction, not just as an option, but as a requirement. The argument is that some of these elements are more necessary in a STEM program because they’re not necessarily part of the formal curriculum. But med students are still human beings, and they’re going to be engaged in vulnerable, high-stakes experiences. They’re going to go out and work on human bodies, and there’s more to it than what they learn in an anatomy lab.”