Table of ContentsClose

More heart care options, less risk

UI Heart and Vascular Center offers highly specialized, less-invasive heart therapies

Traditionally, patients with heart valve disease or other structural heart problems had limited options for care. It usually meant major surgery: opening the chest with a large incision down the sternum. Recovery could take weeks or months, was painful, and required extensive cardiac rehabilitation. And for some patients, because of their age or health conditions, this option was simply too risky.

Today, nearly a decade since the first catheter-based heart procedures were performed at the University of Iowa Heart and Vascular Center, interventional cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons have collaborated to offer a series of highly specialized, less-invasive treatment options.

Advances in technology and specialized training have opened the door to transcatheter valve replacement and repair, minimally invasive surgical options, and other therapies. For patients, this means less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, faster recoveries, and a quicker return to everyday activities.

“We’ve seen a real evolution of these therapies that we’ve worked really hard to develop expertise in and stay on the cutting edge of,” says interventional cardiologist Phillip Horwitz, MD, clinical professor in the Department of Internal Medicine in the UI Carver College of Medicine. “My personal practice has evolved in the last five to 10 years as we’ve branched out into new treatments. It’s really been a fundamental change in what I do on a daily basis.”

Iowa's most comprehensive valve disease care

With the introduction of catheter-based technologies and procedures, UI Health Care created a structural heart disease program to offer patients a one-stop shop to find the best treatment for their condition. Procedures include catheter-based options for aortic valve replacement, treatment of mitral regurgitation with transcatheter mitral valve repair, and valve-in-valve procedures for re-replacement of failing surgical valves.

Patients who are considering their treatment options meet with a cardiologist and a cardiothoracic surgeon, and clinical care decisions are made as a team of providers with expertise in valve care.

A one-stop shop

For patients with valve disease or structural heart problems, the UI Heart and Vascular Center offers the most complete set of treatment options, which include catheter-based valve replacements and repairs.

“What we’re really doing is blurring the lines between cardiology and cardiac surgery and providing care in a collaborative and multidisciplinary way,” says Horwitz, who is the medical director of the Structural Heart Disease Program. “Our cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons complete these procedures together, and a variety of these options can be tailored to what an individual patient needs.”

The UI Heart and Vascular Center has performed more than 1,000 TAVR procedures since 2011, with a success rate of 99%, consistently higher than the national average.

Roughly 2.5% of the U.S. population, or over 8 million people, has valvular heart disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To provide patients with the most complete care, collaboration between interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons has improved greatly, according to Mohammad Bashir, MBBS, UI cardiothoracic surgeon and surgical director of the program.

“We’re able to think alike,” Bashir says. “They’re able to see surgical approaches, and we’re able to look into quicker, more efficient therapies.”

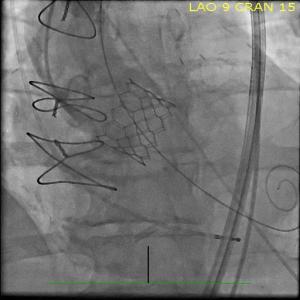

The most commonly performed procedure, transcatheter valve replacement (TAVR), is an option for patients with severe aortic stenosis, a stiffening and narrowing of the aortic valve. The UI Heart and Vascular Center has performed more than 1,000 TAVR procedures since 2011, with a success rate of 99%, consistently higher than the national average.

The TAVR approach uses a prosthetic valve that is compressed onto a catheter. The catheter is inserted into the femoral artery in the patient’s thigh and advanced to the valve site in the heart. The new valve is then carefully positioned and deployed, making it immediately functional.

A recent international trial showed that the outcomes of TAVR and of traditional open-heart surgical valve replacement are similar if not improved with the TAVR procedure.

“In some ways, TAVR procedures are replacing traditional cardiac surgery,” Horwitz says. “They were initially used primarily for folks who were just simply too sick to have the ‘open’ surgical procedures. The evolution has been that even in low-risk patients, TAVR is at least as good if not a better alternative.”

Specialists in the program are also involved in a number of clinical trials that not only help define best practices for the growing field but have also brought in new valve therapies that are currently not performed anywhere else in the state, such as tricuspid valve repair.

For this new procedure, specialists use “clip” technology, which they typically use to fix the heart’s mitral valve. The clip is guided to the heart using a catheter and clamps the leaky part of the tricuspid valve, allowing the valve to immediately start to work normally.

“That’s the benefit of being at an academic medical center: we participate in pivotal research trials that define how these technologies are going to be used. It also enhances our ability to train the next generation of physicians who are going to be performing them,” Horwitz says.

First-in-Iowa procedure offers new option for high-risk patients

When Alan Leff appeared to have run out of treatment options for severe aortic stenosis, the UI Heart and Vascular Center found a new one for him: a highly specialized procedure called transcaval TAVR that had never been performed in Iowa before.

Horwitz and the team used the technique—a technique to bypass the patient’s diseased leg arteries—to replace Leff’s aortic valve.

Before the Aug. 11 procedure, even a short walk left Alan out of breath and weak. Without treatment, the failing valve would have greatly increased his chances of heart failure.

Leff, 84, of University Heights, Iowa, had been diagnosed with mild stenosis about two years earlier, but an exam in May found that the condition had advanced significantly. The valve needed to be replaced soon, but open-heart surgery was too risky.

Because Leff has peripheral artery disease, he wasn’t a good candidate for a standard TAVR procedure. A CT scan showed that none of his arteries would allow reasonable access to the heart using a catheter.

Horwitz recognized that transcaval TAVR offered Leff the option he needed to have the valve replaced. In transcaval TAVR, the catheter is advanced through veins instead of arteries. When it reaches a vein that is parallel to the aorta, the catheter crosses into the aorta, and the artificial valve is placed just like it would be during a standard TAVR procedure. At the end of the procedure, the hole in the aorta is closed with a specialized plug.

Leff had the procedure on a Tuesday and was home by the following Sunday. His walks are no longer hampered by his failing aortic valve, and within weeks he was making noticeable progress.

“I’m to the point where I can walk a block without having to stop,” he says.

But what impressed him the most is how the UI Heart and Vascular Center worked to give him the care he needed.

“Dr. Horwitz could have simply said I wasn’t a candidate for TAVR,” he says. “But he didn’t. He reached out and sought something else for me. It was very gratifying to be working with them. It was a confidence-builder.”

The addition of transcaval TAVR means UI cardiologists have the most complete set of treatment options for severe aortic stenosis, including options for patients with the most complex cases.

A shifting field for surgeons

Just as catheter-based procedures were taking off, cardiac surgeons, like Bashir, started considering how to make traditional surgeries more efficient.

“I was lucky to be able to train in that era when I could see that this field was going to have a lot of changes. I needed to be able to embrace that and take it to the next step,” he says.

That next step was the UI Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery Program, started by Bashir in 2018.

With robot assistance and tiny cameras, a cardiac surgeon accesses the heart through small incisions on the left side of the chest to perform bypass surgery, and the right side of the chest to perform valve replacements and most other heart procedures.

“We’re applying the gold standard therapy, open-heart surgery, but we’re doing it in a less-invasive way,” Bashir says. “We have many patients who are extremely happy now because they were going from one center to another as they simply didn’t like the idea of going through open-heart surgery. They come here because they hear about this approach.”

These patients typically leave the hospital after three days and recover in two to four weeks, according to Bashir, whose practice has shifted significantly toward this new approach. Roughly half to 60% of his cases are completed in a minimally invasive way.

“If it was up to me, I’d do everything less invasively, but some patients bring a lot of medical challenges with them, so it’s not as practical to do it that way for everyone,” he says.

Patient selection is key in all levels of care. For example, younger patients without other complex health issues may experience a greater benefit, over the long term, from open-heart surgery. And now the minimally invasive approach gives them a faster recovery option. Minimally invasive surgeries are also beneficial for older patients allowing them to avoid a large sternal incision.

“This is a niche program in Iowa in that we are the only center that does this in a really efficient manner with a higher volume of patients with complex cases,” Bashir says.

Tony Craine was a contributing writer.

Minimally Invasive Heart Surgery

University of Iowa Heart and Vascular Center surgeons offer minimally invasive heart and thoracic surgery with the state's largest and most experienced physician team in these state-of-the-art procedures.