Table of ContentsClose

Keto diet prevents heart failure in mouse study

Eating a ketogenic diet rescued mice from heart failure, according to a recent study led by University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine researchers.

The study, published online Oct. 26 ahead of the November issue of the journal Nature Metabolism, was one of three companion papers from independent research teams that all point to the damaging effects of excess sugar (glucose) and its breakdown products on the heart. The UI study also revealed the potential to mitigate that damage by supplying the heart with alternate fuel sources in the form of high-fat diets.

Given its need for a constant, reliable supply of energy, the heart is very flexible about the type of molecules it can burn for fuel. Most of the heart’s energy comes from metabolizing fatty acids, but heart cells can also burn glucose and lactate, and also ketones.

Too much glucose, however, has been linked to heart failure, and heart failure is a leading cause of death in people with Type 2 diabetes. Heart biopsies from people with heart failure show an accumulation of sugar molecules in the heart, suggesting that this “backup” of glucose, because it is incompletely metabolized, may be contributing to the damage. The new UI study investigated how glucose and accumulation of these metabolites contribute to heart failure.

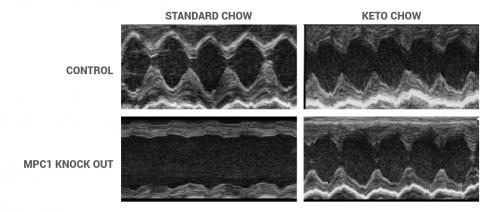

The UI team, led by E. Dale Abel, MD, PhD, professor and chair of the Department of Internal Medicine, removed a critical protein from heart cells in mice. This protein, called the pyruvate carrier protein, is responsible for taking pyruvate, derived from glucose metabolism, into mitochondria where it's further metabolized to make energy. Levels of this protein are reduced in human failing hearts. Removing the pyruvate carrier protein prevents heart cells from using glucose as an energy source and causes a backup of the glucose-derived molecules, similar to what has been seen in human heart failure.

“We found that this was sufficient to cause these mouse hearts to fail,” Abel explains. “If you block this fundamental process of pyruvate uptake for energy, the unused glucose leaks into other metabolic pathways that lead to cell death and damage, and contributes to heart failure. It's really another way of saying that too much sugar is bad for the heart.”

There has been a long and controversial history of studies that counterintuitively suggest that high-fat diets may be beneficial to the heart. As this evidence has built up, there has been a growing interest in testing the effects of ketogenic diets in patients with heart failure, and several clinical trials are ongoing. The UI study used mice to investigate what happened when the mouse hearts that could not process glucose were provided with fats or ketones for energy instead.

The researchers found that ketogenic feeding (a high-fat, low-carbohydrate, low-protein diet) completely prevented heart failure and normalized heart function in diabetic mice. In addition, feeding the mice either ketones alone, or a high-fat diet that was not ketogenic, also rescued failing hearts.

Overall, the study suggested that shutting down the glucose overload by any means was beneficial.

“There's something about too much glucose that appears to be very harmful,” says Abel, who also is director of the UI Fraternal Order of Eagle Diabetes Research Center.

The study doesn’t directly address whether this finding is relevant to heart failure in human patients, and if there are risks versus benefits to the heart of these high-fat diets. Abel says the study findings do not mean that patients with heart failure should start eating a keto diet.

“What I can say is that other studies have shown that when the heart begins to fail, it tends to want to use more ketones. So, it may be feasible that the heart uses ketones to try and rescue the failing heart,” he says. “Studies like ours really add impetus to the current clinical trials of ketogenic feeding in people with heart failure.”

Abel worked with a multidisciplinary team of UI researchers from the Fraternal Order of Eagles Diabetes Research Center and the Abboud Cardiovascular Research Center, as well colleagues from the University of Montreal in Canada, the University of Jena in Germany, the University of Minnesota, the University of Utah, and The Ohio State University.

The research was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, the American Diabetes Association, and Montreal Heart Institute Foundation.