Table of ContentsClose

Since undergoing open-heart surgery at age 2, Iowa City-native Jon Bach has returned for an annual checkup every year since.

When he started coming to University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics to monitor his condition, called tetralogy of Fallot, his doctor informed him that his surgically implanted heart valve would eventually need to be replaced as he grew in size, but he may be able to wait for a new treatment to avoid another open-heart surgery.

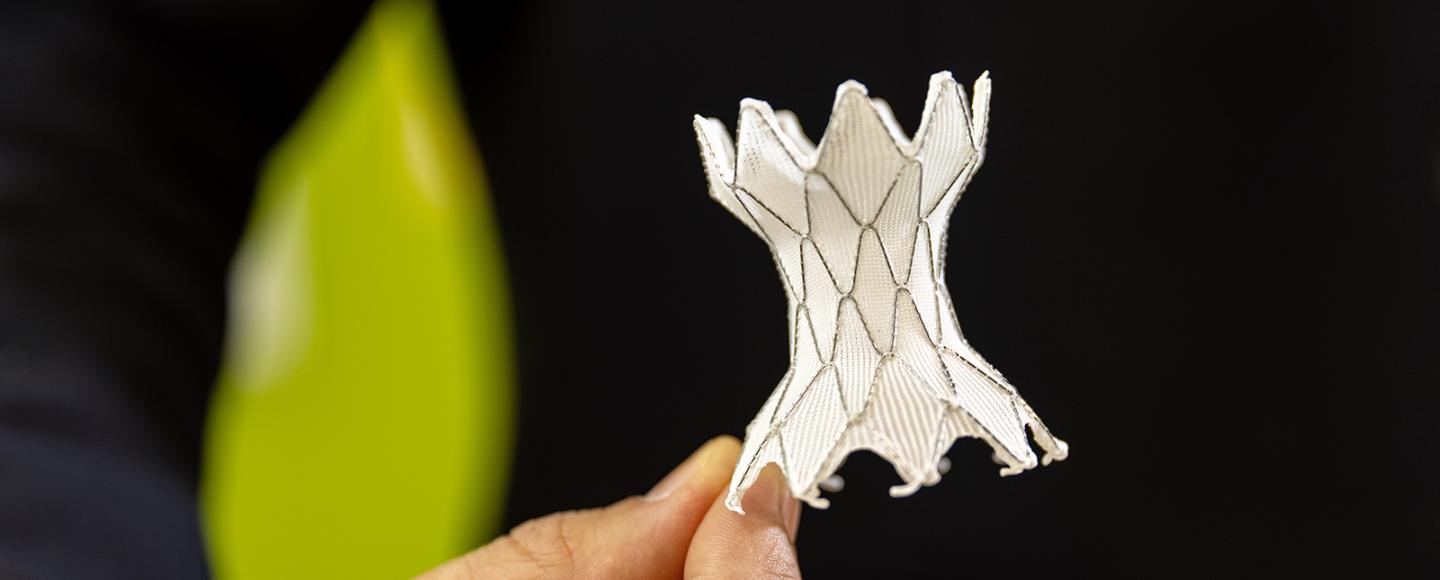

And that proved to be true. In September 2021, Bach’s heart valve was replaced by the new Harmony Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve System.

“I can’t tell you how I relieved I was,” Bach, 48, says. “I was out of the hospital within 24 hours, and there was zero pain.”

UI Health Care is the first in Iowa and only one of a handful of centers nationally to use the Harmony valve for pediatric and adult patients with severe pulmonary regurgitation—or blood leaking backward into the right lower chamber of the heart.

Top cardiac surgery program in the U.S.

Our cardiac surgery program is recognized by U.S. News & World Report as one of the best places in the country for patient care.

Patients with certain congenital heart disease, which disrupt blood flow from the heart to the lungs, may have previously had multiple open-heart surgeries over the course of their lifetime. Osamah Aldoss, MBBS, UI clinical associate professor of pediatrics-cardiology, says the Harmony valve, recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), offers these patients not only a less invasive treatment than open-heart surgery, but also one with less recovery time and fewer restrictions before returning to work or other activities.

The new valve is a catheter-based intervention, Aldoss says, meaning physicians deliver the valve to the heart in a catheter through a vein in the groin. Treatment takes place in the cardiac catheterization lab rather than the operating room.

The advantages of this method over open-heart surgery include the avoidance of opening the chest and putting patients on a bypass machine.

“The need for sedation and pain medications are significantly less, recovery time is significantly shorter, and they can go back to their normal activity within a day or two,” Aldoss says.

The patient population that will benefit most from the new treatment are individuals who were born with tetralogy of Fallot or other congenital heart diseases that required either surgical or interventional procedures that left them with a leaky pulmonary valve.

In the past, a leaky pulmonary valve was considered relatively benign. But that thinking has changed over the past couple of decades as more evidence suggests that a leaky valve can worsen heart performance, causing irregular heart rhythms and even heart failure. Physicians have become more aggressive in treating those patients and provide them with competent valves.

Treatment of these types of congenital heart diseases was already improving before the introduction of the Harmony heart valve, Aldoss says, but the range of eligible patients for less invasive treatment was very limited. The Harmony valve introduction covers a much wider range of patients that otherwise were not a candidate for these less invasive methods of treatments previously.

The Harmony valve is a “game-changer” for patients with congenital heart disease, Aldoss says, noting that the procedure takes approximately two hours and patients are able to leave the next day with a new, fully functioning heart valve.

“It’s a big deal for these patients because they have always been told that they’re going to need surgery, and now they have this new method that can be done way less invasively than what they thought,” Aldoss says. “It’s a great revolution in our field.”

For Bach, who says he’s headed to Utah this summer to test out his new heart valve on a hiking trip, the Harmony valve was a relief because it lessened not only the recovery time of treatment but also the risk.

“Through the whole process, I was just kind of astonished,” he says. “My doctor said that he’s already seen some reshaping in my right ventricle, which means a lot to me.”

Cardiologists have waited for a treatment like this for a long time, Aldoss says, and they’re enthusiastic about the opportunity to offer it to their patients.

“This is really exciting for us. It’s a good feeling when you can provide something for your patients safely and less invasively,” Aldoss says. “In the past, I had to send patients to surgery. Now, I can just offer this to them, and they can go home the next day without a new scar on their chest.”

Adult Congenital Heart Disease Clinic

This UI Stead Family Children's Hospital clinic offers a smooth transition for children to adult congenital cardiology care.