Table of ContentsClose

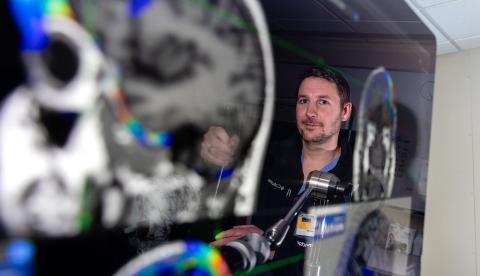

Nicholas Trapp: Leading advances in interventional psychiatry

Clinician-researcher examines neurostimulation therapies to treat brain disorders

Interventional psychiatry refers to a subspecialty centered on the use of new and emerging technologies to treat mental health disorders associated with dysfunctional brain circuitry.

At the University of Iowa, this includes researchers and clinicians in psychiatry, neurology, and neurosurgery with expertise in procedures such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), electroconvulsive therapy, intranasal esketamine, infusion ketamine therapy, vagus nerve stimulation, and deep brain stimulation. UI Health Care is home to one of the country's largest most comprehensive interventional psychiatry programs-providing care for patients from across the state and region with major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, catatonia, and other conditions.

The interventional psychiatry service, in collaboration with scientists at the Iowa Neuroscience Institute and research centers across the nation, gather and analyze brain physiology data to better understand the brain circuits involved in mental health disorders and develop or optimize current or emerging treatment options.

“We’re studying ways to enhance novel treatments for psychiatric and neuropsychiatric conditions,” says Nicholas Trapp, MD, assistant professor in the UI Department of Psychiatry and co-director of interventional psychiatry with the Iowa Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation with colleagues Aaron Boes, (09MD, 09PhD), and Anthony Purgianto, MD, PhD (21R).

In addition to making neurostimulation treatments more accessible to patients, Trapp and colleagues also examine why they’re effective and if they can work better.

“We understand a lot of things about these treatments and how to use them, but we’re still learning in terms of having a full understanding how they work,” Trapp says. “This is partly due to the sheer complexity of brain disorders. One simple goal is to better understand what’s happening in the brain when we deliver a pulse of electrical or electromagnetic energy.”

One aspect of Trapp’s research is to study treatment approaches already in use to see if they can be refined for better efficacy. In a paper published in the September/October 2023 issue of the journal Brain Stimulation, Trapp and his colleagues compared two common strategies—the Beam F3 and 5.5 cm methods—used to target rTMS in treating major depressive disorder. The researchers report that both targets achieve similar outcomes for treating depression. They also found that the 5.5 cm targeting strategy may have a greater effect in treating anxiety symptoms compared to the Beam F3 approach, but more research is needed.

“We can tease out how different networks involved in depression may be abnormally connected and use that to better understand patient symptoms and how to treat them,” Trapp says.

Trapp also has established an interventional psychiatry registry in collaboration with his UI colleague, Mark Niciu, MD, PhD, which allows patients receiving treatment to opt into additional tests and imaging-producing data that can be used to inform and develop future clinical trials. Researchers can look for biomarkers that may indicate a specific response to treatment, such as imaging studies that measure brain activity, energy consumption, and connectivity, for example.

This information can help Trapp and others develop and apply precision medicine approaches to care.

“All of these are ways of trying to help us determine the profile of a patient who will respond to TMS or esketamine, for example,” Trapp says. “If we can better identify who will benefit before they go into treatment, we can save time and resources and forgo any time wasted on therapies that we know won’t work.”

The team is currently enrolling participants in a new study for cerebellar TMS involving patients with schizophrenia and patients with autism as well as patients without these conditions, comparing how patients respond to a short course of the treatment. Further studies in subjects with depression and suicidal thoughts are planned in the near future.

Advancing new technologies and treatments for brain disorders using noninvasive brain stimulation while providing the latest treatment options for patients and training the next generation of scientists and clinicians is challenging work, and Trapp is encouraged by how far the field has progressed.

“We have a much better understanding now than we did 10 years ago,” he says. “And we’ll know even more 10 years from now than we do today.”

The Trapp Lab

The Trapp lab focuses on the application and optimization of neuromodulation therapies for the treatment of neuropsychiatric conditions.